BACKGROUNDER Thermal Energy Storage: What exactly is it?

We take a shallow dive with research scientist, Wayne Groszko, into a technology that holds a key to not only our ability to access cheaper, cleaner energy, but to do it in a way that supports our utilities’ efforts to avoid the need to turn to fossil fuels during periods of high energy demand.

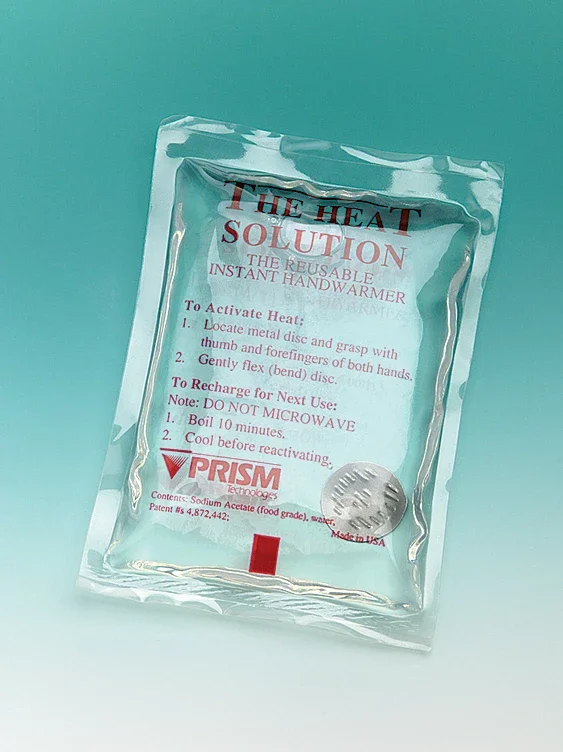

A handwarmer, and a perfect example of a TES change agent product - in this case, using sodium acetate trihydrate. Photo courtesy of Flinn Scientific.

A term we sometimes hear mentioned these days is Thermal Energy Storage (TES). One of many technologies to help us get to a greener future, it’s not as new as you might think — instead very much hiding in plain sight for centuries. But for our purposes, it’s a technology that’s been available for the last few decades, despite being relatively unknown by most people

So what exactly is TES? In a nutshell, it’s capturing heat or cold for later use. The how’s and the why’s require a little more explanation.

In Nova Scotia, as in many areas of the world, we’re trying to use our energy grid in the wisest way possible. In this scenario, “wise” meaning accessing energy during non-peak hours for later use (during the more expensive, higher demand times).

Nova Scotia Power defines prime heating season as December to February, where off-peak, mid-peak, and peak rates apply. For all other months (March to November), only mid-peak and off-peak rates apply. The idea is to store energy at the cheapest rate; at the moment that’s between 11 pm and 7 am during the week and anytime during weekends and holidays.

So, what are the current thermal storage options for both residential and commercial customers? Wayne Grozsko, research scientist with the Nova Scotia Community College’s Applied Energy Research Lab, says there are a few either well established or close to market-ready systems deserving of a closer look.

“The standard electric thermal storage units that have been available for a long time typically have a ceramic material in them, and there’s an electric resistance heater in those that heats up to a very high temperature,” he says.

These electric thermal heaters sit in an insulated box waiting to be activated, with their heat sent to a heat exchanger where it then produces hot air in the house.

Another common form, says Groszko, is storing heat in an electric hot water tank.

“There you would basically have a controller that would make sure the hot water tank is on and in some cases even boost the temperatures of the tank when electricity is plentiful, and then at peak demand, times when you’re trying to save electricity, it shuts off the heating elements, allowing you to ‘coast through’ whatever is already stored in the tank, “ he says.

Efficiency Nova Scotia currently offers free hot water controllers for participants in their Eco Shift demand response program. See our August 2024 article, The next clean frontier, for an expanded discussion with Wayne Groszko on the untapped potential for energy savings in the 160,000 water heaters in this province.

Alternately, Groszko says that through studying hot water usage in Halifax it was established that the vast majority of customers would never notice if you simply turned off their hot water heater for four to six hours during that peak demand time, as they had enough water in the tank to cover their daily needs.

Electric thermal storage heater. Photo courtesy of Efficiency Nova Scotia.

A third category of TES products is through the use of something called phase change materials. Think a type of handwarmer, which, when heated (typically boiled), returns to its liquid form, then releases that heat once activated and as it returns to a semi-solid state, releasing the heat it absorbed through the melting process. That material is called sodium acetate trihydrate, and Groszko is excited about its potential to be a big player in the thermal energy storage game.

“I would say the technologies to use it for home are definitely in the works,” he says. “Companies like Stash Energy, here in Canada, have a heat storage unit based on that same change agent material, that when coupled with a heat pump combines the energy efficiency of a heat pump with the energy storage potential of a phase change material.”

Finally, says Groszko, is the uncomplicated but extremely efficient in-floor radiant heat using concrete floors, which has also been around for decades.

Beyond the financial savings for both residential and commercial customers is the ability of TES to help fight climate change. By easing up demand during peak hours, it can reduce the need for utilities like Nova Scotia Power to “burn fuel — oil or gas — in a bunch of extra generating stations,” he says.

“And those tend to be some of their more expensive generators.”

Nova Scotia will soon be creating more clean wind energy than we’ll know what to do with, so, finding good storage solutions for that energy — including ETS solutions — will be key to moving away from fossil fuels.

“The technology exists but still needs to be integrated into a seamless system where the customer doesn’t have to think about; having a system in place where it’s easy for the customer to adopt and where they get some kind of benefit — doesn’t have to be huge, but they need to see it as a good thing for them.”

And what’s the cheapest heat source at the moment? Well, says, Groszko, that’s still the heat pump.

“Due to the high efficiency of the heat pump, you basically get three units of heat for each unit of electricity you spend on it, as opposed to a ceramic resistance heater, for example, which gives off only one unit of heat for every unit of electricity.”

Climate Stories Atlantic is an initiative of Climate Focus, a non-profit organization dedicated to covering stories about community-driven climate solutions.

Sign up for notifications of our latest free articles. You can unsubscribe at any time.